‘The deadliest drug’

From the time he could walk, Cooper Davis was off and running. An adventurous, outgoing kid, Cooper was an explorer, a risk-taker, his mother, Libby Davis, says.

For the 16-yearold, there was no such thing as too high or too fast. He was fearless. “He was super outgoing to a fault, and he didn’t want to fit the typical teenager mold,” Libby said. “He was into extreme sports. He was the type of kid who wanted to follow his own set of rules.”

On a warm Sunday afternoon on Aug. 29, 2021, Cooper, who had just started his junior year at Mill Valley High School in Shawnee, was hanging out with three other boys at a Shawnee home. The boys decided to share two blue pills they thought were prescription Percocet. Cooper took half a pill.

“I got a call from the Shawnee Police telling my husband and I we needed to get to the address as soon as possible,” Libby said. “When we arrived, paramedics were in the house working on him, so we stayed outside and someone would come outside and give us updates. They had already been trying to resuscitate him for close to 40 minutes and had given him several doses of Narcan. They did see something on the monitor, something with his heart rhythm, that gave them hope, so they transported him to the emergency room.”

As emergency room staff continued working on Cooper, a physician updated Libby and her husband on their son’s condition. Some of Cooper’s lab results hadn’t registered during a previous test, and so the doctor ordered another. Like the paramedics, the physician had also seen something that gave him a glimmer of hope. But before the doctor could finish his sentence, Cooper’s vitals began plummeting, Libby said.

They couldn’t bring him back.

“Cooper was certainly no angel,” she said. “But he wasn’t a drug addict. He had previously experimented with weed and smoked it from time to time, but never took any hard drugs. That’s what we were trying to keep him from doing.”

At the time, Libby and her husband were drug-testing Cooper, who was using synthetic marijuana to pass the tests, she said. When her son died, Libby thought it was the result of the synthetic marijuana use. While she didn’t know a lot about the drug, she was told by Cooper’s girlfriend that the synthetic version would fry someone’s brain. But because his parents were trying to prevent him from using pot, Cooper tried to circumvent a positive test result by using the synthetic kind. It wasn’t until six to eight weeks later that toxicology results confirmed the only thing found in his system besides caffeine and the Narcan, used in the hopes of reviving him, was fentanyl.

“As I’ve learned over the last year, there’s definitely a correlation in our youth population between their emotional health and the ease of obtaining pills off social media,” Libby said. Teens are self-medicating. We’re a pill-popping nation, and it’s pretty socially acceptable. With these teenagers, while they’re not doing the hard drugs, they feel that taking a pill is not that big of a deal. They see pills in their homes. They see their friends using pills for various reasons, so I feel they turn to this because they don’t want to bother their parents. They don’t want to talk about their mental health. They just want something that they think will truly help them relax, study for a test, escape the world for a little bit, whatever it is – the reason in their mind seems harmless. The pills are easy to get, so they just go that route. Or on the other hand, you have the curious teenager, our mission is to educate parents and families and students on the new dangers of drugs because this isn’t something we knew about five years ago. We had lost a close family friend 10 days prior to Cooper’s death, also a 16-year-old friend, I really think, and I don’t say this publicly very often because I don’t want them…in no way do I want our family friends to think that it was their fault, but I do think he was sad, and I think he wanted to escape.”

Libby said she thinks it was a combination of factors that resulted in Cooper taking half of that laced pill.

“He wasn’t trying to do anything extreme, but unfortunately with illicit drugs like fentanyl, he got enough of the fentanyl to kill him,” she said.

In the months following their son’s death, the couple, who both work in health care, couldn’t understand how they hadn’t heard about the fentanyl epidemic. That’s when the two decided they needed to approach Mill Valley High School administrators about warning students about the dangers of taking fake pills. Libby says it started with a sticker, a campaign for teens, pledging to stay drug-free. She called it Keepin’ Clean for Coop. The couple helped coordinate student and parent education events by contacting local U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agents to provide information and tell Cooper’s story. A friend helped Libby create several social media accounts to promote the campaign, and by February they established a foundation under the Greater Kansas City Foundation umbrella. In August, Keepin’ It Clean for Coop was formally designated as a nonprofit. The group has already hosted its largest fundraiser a Fighting Fentanyl 5K, which raised $23,000 to help fund scholarships, education events and assist teens, who might be struggling with their mental health.”

“To us, it’s not about the money we raise,” Libby said. “To spread awareness, we have to use our voices.”

Libby is also working with her sister-in-law, a nurse practitioner in Wichita, as they visit schools to tell Cooper’s story. By mid-November, they had given more than 29 speaking engagements, reaching more than 5,000 people.

“Our passion is to use Cooper’s story as a cautionary tale and to continue to get the word out,” she said.

Libby says she works closely with DEA officials and took part in a DEA-sponsored national summit in Washington, D.C. in June as well as regional event this fall in Leawood. She’s also been working with U.S. Sen. Roger Marshall (R-Kansas) helping develop legislation he introduced to hold social media companies more accountable. Marshall’s team reached out to Libby in May and asked permission to use Cooper’s name in the legislation. Believing the bill would save lives, she didn’t hesitate. Known was The Cooper Davis Act, the bill would require social media companies and other service providers to take a more active role in working with federal agencies to combat the sale and distribution of drugs on their platforms. The act would also require social media companies to report information on illegal drug sales, which could be used by the DEA to intervene before a transaction occurs, or on a larger scale, uncover criminal drug networks.

“(This) should scare everyone,” Libby said. “Then there’s people who say, ‘Oh, don’t use the fear tactic.’ I don’t know how you can present these facts and not have it be construed as a fear tactic because everyone who hears these facts should be fearful. It can happen to any family in America, and it’s not getting any better. There’s still too many people who don’t know, and we need to be talking about it.”

“The Deadliest Drug” The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has deemed fentanyl as the deadliest drug currently facing the U.S. A highly addictive synthetic opioid, the drug is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine. Just 2 milligrams of fentanyl – an amount so tiny it could fit on the tip of a pencil – is considered potentially deadly.

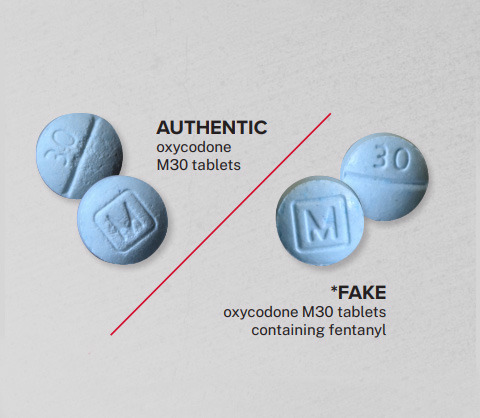

Earlier this year, U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration agents focused their efforts nationwide, targeting the trafficking of fentanyl- laced counterfeit pills. In a little more than three months, agents seized 10.2 million fake pills in all 50 states, DEA officials said – about half the amount of pills seized during the entire 2021 year.

First developed in 1959, fentanyl was introduced in the 1960s as an intravenous anesthetic. Years later, the pharmaceutical- grade fentanyl was developed for pain management in cancer patients and delivered through a skin patch. According to federal officials, fentanyl works by binding to the body’s opioid receptors, which are found in the parts of the brain that control pain and emotions. The drug can cause everything from extreme happiness and drowsiness, to sedation, addiction, respiratory depression and arrest, unconsciousness, coma and even death.

In 2021, nearly 108,000 Americans died of drug poisoning. Of those, nearly 66 percent involved synthetic opioids. According to the DEA, Mexican drug cartels are responsible for the majority of the fentanyl-laced pills being trafficked into communities throughout the United States. In late-November, the DEA alerted the public to a recent finding that, of the fentanyl-laced prescription pills analyzed this year, six out of 10 contained a potentially deadly dose – a sharp increase from 2021 when four out of 10 were likely to contain lethal levels.

DEA Administrator Anne Milgram spotlighted two Mexican drug cartels, the Sinaloa and the Jalisco cartels as mass-producing the deadly look-alikes to prescription drugs, including OxyContin, Percocet and Xanax, using chemicals primarily sourced from China.

In 2021, there were 678 overdose deaths in Kansas, with poisonings resulting from various drugs listed as a contributing factor. More than half of those – 347 – were attributed to synthetic opioids, according to the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. In 2020, Kansas had only 161 synthetic opioid-related deaths. From 2012-2021, Franklin County had 33 drug-related deaths. During the same period, seven were attributed to synthetic opioids.

“If you look at the numbers and the way that it’s tracked for reporting purposes, we assume it’s fentanyl, but the way it’s tracked it’s reported as a synthetic opioid,” Franklin County Sheriff Jeff Richards said. “It could be any synthetic opioid, but what we’re seeing is fentanyl. In that category, you can see how it’s been an issue in Kansas over the years, but in 2020 there was big spike and again, an even bigger spike in 2021.”

The most current data available for Kansas is from 2021. Richards said the sheriff ’s office isn’t always notified of every incident, especially those where an individual is dropped off by a friend or family member at a local hospital. In those instances, hospital officials notify the state, he said.

According to other state overdose data, as of October 2022, Franklin County was still within its three-month average of six poisonings occurring each month. While a few Kansas counties did see lower numbers, others reported an increase in local overdoses.

“So, from our perspective, we do know fentanyl is a much bigger deal so all of our people carry Narcan and everyone is trained to use it,” Richards said. “We have it for our staff so when we respond we can administer it. It really changes the way we do our job. We have to operate under the assumption that any powder we recover is fentanyl or laced with fentanyl. According to the lab reports we’re getting back, fentanyl is in just about everything tested. Even meth has fentanyl in it. So that is an issue for us. So when we’re packaging it, we’re making sure deputies are wearing a mask, gloves and making sure they’re taking precautions.”

Because the drug is so potent, evidence submitted for testing at the Kansas Bureau of Investigation criminal laboratory must indicate the presence of what could be fentanyl.

While overdose deaths have spiked, Richards said in cases where fentanyl- laced pills are involved, law enforcement officials refer to it as a poisoning instead, because most of the time, people don’t realize what they’ve actually ingested.

“The problem with it is depending on who is cutting it, and using it to cut whatever the other drug is, you don’t know what amount they’re putting in,” the sheriff said. “So someone might take a certain amount of meth at one point, and then they take the same amount next time to try and get the same high, well now it’s got twice as much fentanyl in it as what it had before, and now it just shuts them down and they stop breathing. Fentanyl has a purpose in a medical facility, but it’s highly regulated. But on the street, there’s no regulating to it. They don’t know how much they’re taking. They don’t know what the purity level of it is. They don’t know any of that. That’s why it’s killing so many.”

While Narcan initially revived a person quickly, Franklin County Undersheriff Kiel Lasswell said today multiple doses are administered to get the same result.

“Nurses are pumping them with Narcan, and it’s not doing anything,” Laswell said. “They’re not necessarily shutting down completely, but it’s not waking them up anymore. I don’t why. I don’t know if it’s the difference between the synthetic and the street grade-like stuff that they’re doing, or the amount they’re putting in their bodies, but we’re seeing a little bit more difficulties with Narcan.”

In May, Richards joined U.S. Sen. Marshall and a few other select Kansas sheriffs at the southern border near McAllen, Texas, where they toured the area and met with U.S. Border Patrol and Texas Department of Safety officials. The trip, Richards said, gave him a chance to see the technology and techniques used to detect drugs smuggled into the United States. On the flip side, he witnessed methods used by smugglers to defeat drug detection efforts.

“From what we’re seeing up here, once they get (drugs) into the United States and through those checkpoints, they’re getting distributed out the way they always were,” Richards said. “It was very interesting to see the lengths they were going through to get them in. About a month ago, I met with Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, and we talked about the border and everything that’s pouring across that border. It was interesting to me when we were down there on our visit, we were so busy with Border Patrol and Texas Department of Safety dealing with the massive number of people coming across that while we were dealing with those groups of people coming across, there would be a detection where there were people in vehicles headed north at another location. But no one could get to them because everyone was tied up over here with this distraction. You don’t know who those people are. You don’t know what it is that they’re transporting. Homeland Security is saying they believe that most of the fentanyl is coming in at checkpoints – that they’re just getting past our technology and getting past everything we have in place – whether that’s true or not, I don’t know, but that’s what we were told. Either way, it’s coming up, coming across that border whether it’s going through a checkpoint or going around. Common sense tells me it’s not coming through those checkpoints, it’s getting around while everyone is occupied with other things.”

“We have 35 miles of I-35 that go through our county, and if you look on the map of where the bigger numbers are, they’re in the metros,” Richards said. “I-35 goes up through Wichita, which has a very large concentration of overdoses and poisonings, and then Johnson County and Wyandotte and right up the road, and we’re in the middle of those. It’s the same highway where it’s all coming through. It’s important from our aspect to detect those things. What we’re experiencing is most of this stuff goes up to cities north of us, and once it reaches its destination through the distribution network, then that’s when your dealers are getting it and then it filters down here.”

In mid-October, the Kansas City, Mo., Police Department responded to four confirmed fentanyl overdose deaths, including a toddler, in a 13-day timespan, along with several other suspected fentanyl deaths, and 17 nonfatal overdoses. In September, KCPD’s Drug Enforcement Unit seized four large amounts of fentanyl, including more than 17,000 fentanyl- laced pills and another two kilograms of fentanyl powder. The department’s largest seizure this year, as of this fall, is 41,000 pills. The unit has also seized fentanyl in brick/kilogram form.

While sheriff ’s officials have not seen the rainbow-colored pills, which were in the news in the months leading up to Halloween, Lasswell said investigators have seen similar fake pills, including some M30 tablets that were produced in different colors, but not necessarily the vibrant pills in pastel colors, such as pink and purple.

Recently, the sheriff ’s office dealt with a young man, Richards said, who overdosed on fentanyl- laced pills. During the course of their investigation, deputies were able to trace the pills back to a dealer in Topeka, who was later arrested in connection with the poisoning.

“We don’t want people using harmful substances anyway, but right now it’s even more dangerous because they don’t know for sure what it is they would be putting into their body,” Richards said. “And it could be something that’s going to kill them.”

“It’s just so unpredictable and harmful that you just don’t know,” Lasswell said. “That last dose could be your last dose.”

Ottawa Police Chief Adam Weingartner knew fentanyl-laced pills would eventually make their way to the Midwest. It was only a matter of time. While the drug isn’t as prevalent as meth, it is starting to become more readily available. As a result, his officers also trained to administer Naloxen, another medicine similar to Narcan, and have it readily available.

“It’s a life-saving measure, and it’s almost becoming so common that it’s just a part of an opioid investigation,” he said. “(This fall,) a drug poisoning arrived at the hospital’s emergency room. When the officer arrived, the emergency staff was trying to resuscitate and doing CPR, the officer handed Narcan to the nurse who administered it. It was able to reverse the effects and turned it around and likely saved a life.”

Weingartner said officers are seeing drug poisonings/overdoses at least once a month, on average.

“When we see our first overdose, I tell staff to prepare for more to follow,” he said. “Many times, people have no idea what they’re taking and think it’s something else. Up until last month, we didn’t see the multicolor pills. We know through investigations that those pills are here. It’s much sooner than we anticipated, but we do know that they’re here.”

“Locally, I feel it’s in the early stages, much like we saw with meth with the manufacturing and distribution, but I believe it will only get worse,” he added.

When Ottawa police respond to a drug poisoning, Weingartner said the agency investigates it as a homicide. The department has already had two fatalities, one this year and another in 2021 – both of which are being investigated.

“We will still investigate, and we will hold people accountable for the death of someone else,” he said.

“People just don’t know it was fentanyl,” Weingartner said. “Often, they find out too late, or they find out after friends and family find them. If you take drugs, there’s an increased chance it contains fentanyl. A lot of the people we’ve talked to tell us they didn’t know they were taking fentanyl. They had no