Family: This time it really is all about blood

I am not a hero. Despite what my boyfriend says about me. Or my family.

And no, I will not be breaking out into singing Taylor Swift’s new hit song, “Anti-Hero”, either.

It took me awhile to push back emotions and some writer’s block to share this piece with the world per everyone’s request. Normally, I prefer writing about the news outside my personal realm but was told that as a member of the community I had now become my own news story.

A journalist never wants to be the story. I would rather be behind the pen and paper.

On Wednesday, October 18 at KU Medical Center located off of Rainbow Boulevard and 31st Street in Kansas City, I had two holes drilled into my hips for a bone marrow procedure to try and save my younger brother Erik from the Chronic Myleoid Leukemia he had been battling since 2014.

In my family, I had spent my entire childhood surrounded by sick, disabled or strong caretakers. “Family is everything” in my hardworking, lower middle class, Midwest, Scandinavian family. You didn’t bat an eyelash to help each other out. It wasn’t a big deal. You just rolled up your sleeves and showed up unannounced with casseroles or cleaning gloves or muscles to help transport Great Grandma in and out of her wheelchair. I spent a lot of time in nursing homes from a very young age and around older relatives. I’ve been repeatedly told over the years what a “tough cookie” I am and how I am a born empath. I am not sure. I am not that tough. Taking care of each other is all I knew.

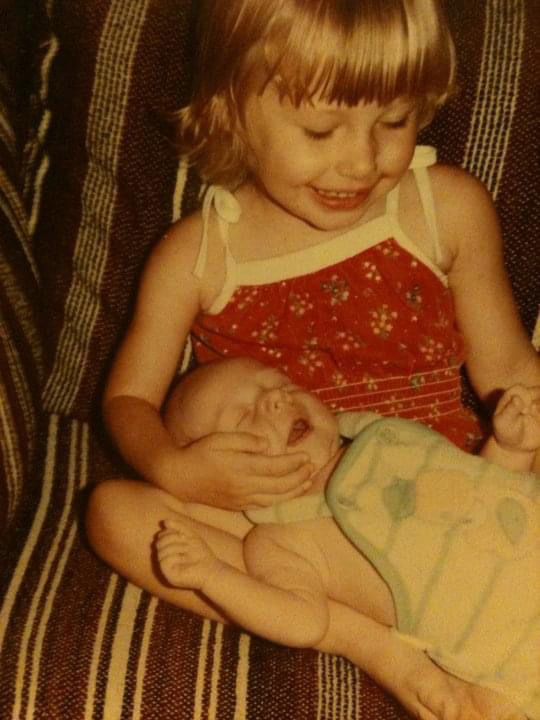

So when the time came for my brother to need a bone marrow donation, I didn’t hesitate. He has a fifteen year old daughter excelling in the teacher academy at Olathe East High School. My niece Isabella, whom I adore. She needed him. We all needed him.

It all began at the end of 2021, when we received the call that the meds my brother had been taking to keep him alive and stable since his diagnosis in 2014 were no longer working, and we needed to consider a bone marrow donation. We first met with doctors and advocates in January who overwhelmed our emotions and brains with an abundance of information. But we thought we had more time. You always think you have more time. And we did until this Fall arrived.

Chronic Myleoid Leukemia is a slowly progressing but uncommon blood cell cancer that begins in the bone marrow. It is caused by a chromosome mutation that occurs spontaneously. The Philadelphia chromosome is a rare chromosome found in CML patients. My brother has the chromosome. It is not hereditary. The American Cancer Society website states the leukemia cells grow and divide, and build up in the bone marrow until they spill over into the blood.

There are fewer than 200,000 cases per year. Early symptoms are bleeding easily, feeling rundown or tired, weight loss, pale skin and night sweats. The optimal life span is ten years. My brother had hit year eight as I prepared to give my bone marrow a month and a half ago.

I couldn’t write this until I knew with some more optimism that the procedure was working. My family still doesn’t know what the outcome will be, but every day becomes more and more positive for him to be included as a positive survivorship rate statistic.

There were no matches in the database system KU medical officials combed through twice. Siblings and children are typically the best matches for a bone marrow donation, and we weren’t about to put my niece through the ordeal. As I said before, I didn’t hesitate. However, I wasn’t a full match either. I was considered a half match as I only met seven of the key data points the doctors were looking for.

A haploidentical transplant is a type of allogeneic transplant. Doctors use healthy, blood-forming cells from a halfmatched donor to replace the unhealthy ones. My blood was tested to find human leukocyte antigen type blood cells. Even though it is a highly effective treatment option it is still a high-risk procedure with a significant chance it wouldn’t work. It was the only hope we had.

So after nine months of meetings with his KU medical team led by Dr. Joseph McGuirk and my medical team and advocates, I sat on a hospital bed in one of those flimsy gowns we all love waiting for the anesthesia to take place and the procedure to begin. I probably appeared calm outwardly, but inside I prayed my epilepsy wouldn’t take over, and I would wake up to cure my brother from a disease that had taken over our lives the last eight years.

The procedure of drilling two holes into my hip bones was relatively short. I believe it was less than an hour. The giant ace bandage strapped around my back for the next few days was more of a nuisance. The first shower I would take would be the best shower of my life. The pain was bearable. My throat, however, from the breathing tube was excruciating, and I had no voice for two days. When my mom drove me home, I growled at her from lack of a voice box trying to get a Sprite from the nearby Wendy’s. I was desperate to coat my throat with anything, as it was the worst case of “strep” I had ever endured. It was still better than the other option in my opinion that I didn’t end up qualifying for: Apheresis.

My Mom and I had visited the lab for this procedure a couple weeks before. This procedure requires being hooked up to a machine where the blood plasma is removed for a few hours a couple days in a row. Stem cells that are needed are separated out. The machine is essentially a centrifuge with its own side effects for the donor and patient. The man donating that day I met was very cordial, and I learned a lot. However, in my mind I knew bone marrow extraction from my hips was going to be the better option for my body, and for my brother’s outcome.

I had the next week off to recover. Not being able to do anything was a mostly new concept for me. I had spent the past 11 years raising my niece, taking care of my Dad with Parkinson’s and assisting my Mom. For a time my Dad’s Mom had also lived with us and my Mom’s Dad resided at Vintage Park, where we visited every day. Now I was the patient, and I struggled. In my head the pain and numbness from my hips down through my legs was nothing, but then I would try to walk or sleep. I loudly groaned going up and down stairs. I walked like I was 90 years old. I spent the first day upright sleeping on the couch watching bad sitcoms and cartoons. I stressed about the paper even when I was told not to worry.

The fatigue hit me harder than I expected. One day I felt fine and would overdo it with activity. The next day felt like I had been hit by a semi-truck or two. I couldn’t even get out of bed. I slept a lot. The brain fog was brutal. I am not sure I knew what day it was that first week.

But I was not only the bone marrow donor for my little brother, but his designated caretaker too. I fought through it in order to prepare for my brother’s homecoming. He spent a month in the hospital doing all the hard work. Every day he was poked and prodded and tested. The month he lived in the Cambridge tower was the roughest and is the riskiest part of the entire process, as his entire immune system had been stripped, as they put in mine. And we prayed I wouldn’t attack him, even though that would be a typical sibling move, as Graft versus Host disease is at the highest risk of occurring the first month out from the transplant procedure. It can be mild or severe. It can happen at any time still. Luckily, we have dodged that bullet so far.

I would be my brother’s bone marrow donor again in a heartbeat. Despite the fact that his doctor Dr. McGuirk was hesitant at first to proceed with the transplant. He didn’t think we were going to take it seriously I feel, because my brother and I have always handled hardships with sarcasm or jokes. Or maybe it was my brother’s past history of alcoholism and drug use. I am grateful that we had one of the best oncologists in the nation, along with the care team. Dr. McGuirk was honored last month by Representative Sharice Davids for his advancing cancer research work.

I am grateful that we had the opportunity to have the transplant procedure at one of the nation’s best hospitals with the best doctors. My parents have cried and expressed their gratitude for their 42-year-old daughter being their son’s match and giving them the best Christmas gift.

The transplant procedure was just the beginning. The week after my brother was released from his hospital stay was the hardest with five-hour appointments and more every day, taking care of a teenager with a packed academic schedule, caring for my 65 year old Dad— which isn’t easy even on the best days and could be a whole entire book by itself with Parkinson’s, and my Mom and I being the only main drivers with full time jobs. Then there is the constant bombardment of rules, constant cleaning, detailed food prep and trying to bubble wrap my brother from all the germs.

That story of the ups and downs and scares we have endured since Thanksgiving will have to be another story for another week’s paper.

But for now, Christmas looks different for us this year. My gratitude for the patience of my employer, co-workers, community, those I serve as your “favorite” local reporter, friends and family, God and all the KU Med doctors, nurses and staff runs deep.

I look forward to my niece having many more years with her Dad. I look forward to another Christmas with us all together. The season of perpetual hope has an entirely different meaning this year.